Innovation as Tradition

The discourse around Octopath Traveler points to what might be called a misremembering over generations; though the game was marketed — and indeed was praised — as a “throwback” and as “nostalgic,” can anyone actually bring to mind a specific 16- or 32-bit era JRPG set in such a generic fantasy world? No: we remember frog knights fighting alongside robots from the future; swords wielded by gun grips; advanced technology coexisting with magic; even sentient (and malicious) slimes with eyeballs. The defining titles of the genre are memorable for their novel characters and settings, surprising twists on fantasy and science fiction tropes, and unflinching oddness. Octopath Traveler, with its squarely medieval world and its cast of self-serious archetypes, exhibits no ambition of being a “throwback” in this particular sense.

If not the world-building nor the characters, it is up to the gameplay of Octopath Traveler to inspire players to fondly recall the formative years of the JRPG, a task in which it largely succeeds by cherry picking various aspects of other combat systems to create a unique rhythm of its own, and one in which familiar character roles, such as healer and thief, are galvanized thanks to a complex interdependence of skills and systems. This kind of innovation, especially with regards to battle systems, is the truly nostalgic element, because innovation through experimentation has always been the one consistently definitive characteristic of the JRPG.

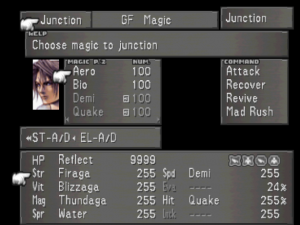

The Final Fantasy series is perhaps the most clear evidence of this unceasing experimentation. The ATB system became a staple after its first appearance in Final Fantasy IV and was an impactful departure from the strictly turn-based mechanics of not only previous Final Fantasy titles, but also of other notable JRPG series at the time, such as Dragon Quest and Breath of Fire. Still, the ATB system is featured in less than half of the series’ numbered entries, and was accessorized in subsequent games with so many new customization mechanics — Jobs in V, Espers in VI — that the gameplay experience of each is wholly unique. More significant still, the audaciously high-concept overhaul of progression and customization between VII and VIII shows that inventiveness and novelty remained priorities for the developers even when creating a follow-up to the most successful and influential game in their flagship series.

Similar to the way in which the ATB system solidified Final Fantasy’s brand for a time, the vast majority of RPG titles for the fourth console generation defined themselves through innovation. The first outings of Star Ocean and Tales incorporated elements of action-adventure and fighting games, respectively; Super Mario RPG added limited real-time input in the form of timed attacks; Lunar introduced spatial elements (area of effect, movement range). The other most popular genre of the 16-bit years — the side-scrolling platformer — remained comparatively static in essential design; variances in control style and move set separate an SNES Donkey Kong game from a Mario game, for instance, but each one of the three Donkey Kong Country titles plays fundamentally the same way. In contrast, SNES JRPGs are unified by some essential characteristics but stand out from one another by virtue of their distinct battle and customization mechanics. This exciting offering of new gameplay experiences became the primary allure of the genre for players.

All of these innovative elements continued to expand and be repurposed in the PlayStation’s impressive rollout of JRPGs. Valkyrie Profile and Legend of Dragoon each took different approaches to evolving the implementation of timed button presses; Grandia riffed on the ATB concept by allowing attacks and skills to affect the flow of the active time meter itself; Final Fantasy Tactics fused mechanics from several games in its parent series with a completely new genre. More interesting yet are the games of this generation that began to completely overhaul the conventions that were inevitably forming around the JRPG — Persona 2 and the SaGa Frontier titles, for example, reimagined fundamentals of design and progression and rebuilt them from the ground up. The first stirrings of three-dimensional gaming appear to have opened the doors for ever-wilder experimentation and, more importantly, the community of JRPGamers seems to have met that potential with not only a tolerance but a taste for it, creating enough demand for innovation to continue as a genre-defining trend.

The PlayStation 2 RPG library was inhabited by many sequels to the innovative games to grace its predecessor, a fair number of which took the stepwise approach to innovation: upgrading to fully three-dimensional models and camera work while only slightly, and often predictably, pushing the established battle system of any given IP forward (as in the case of Valkyrie Profile 2: Silmeria, Grandia 2 and 3, and Star Ocean: Till the End of Time). Other series used the new hardware as an opportunity to think outside the box, with Final Fantasy leaving behind the ATB system and the SaGa series gleefully and recklessly reimagining itself as a digital tabletop RPG with notoriously opaque and unwieldy systems in what can now be called a one-off, the infamous Unlimited SaGa. Persona likewise opted for gut renovation but did so much more successfully via a genre mashup. Kingdom Hearts also attempted a big-budget genre mashup, answering the question, “Can one navigate a real-time ARPG system entirely through an on-screen battle menu straight out of a Final Fantasy title?”

It is also worth noting that the nearly identical gameplay and structure of Persona 3 and 4 is an anomaly not only of this console generation but arguably in the RPG genre as a whole. What other turn-based JRPG series features back-to-back entries using the same engine, combat mechanics, and even some assets? However, the main point to be made from this survey of the PlayStation 2’s JRPG library is that, once again, more robust hardware leads to more robust experimentation.

The last batch of dramatically innovative JRPGs coincides with the seventh generation of consoles and can be attributed to two factors: first, the huge jump in hardware capabilities — and the transition to HD — of the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360; and secondly, the emergence of new methods of control on Nintendo’s Wii and DS.

Developers tri-Ace and tri-Crescendo led the charge on the home console front, taking full advantage of the new hardware to more dramatically intersect real-time and turn-based playstyles. Star Ocean: The Last Hope not only amped up the chaotic sensation of the series’ combat but also rewarded intricate positional strategy therein. The tutorial for the combat is bluntly presented and is not only lengthy and challenging but also very much set up as an interactive instruction manual; this indicates the degree to which tri-Ace was determined to push innovation even to the point where series veterans would need to do some learning to keep up.

Eternal Sonata used a more traditional method of drip-fed tutorials, but took the extra step of literally altering certain tenets of the combat at set intervals of a single playthrough (in a more traditional design, one can imagine the combat of each chapter being categorized as different difficulty settings). As one progresses through the game, the live countdown to the end of a character’s opportunity to take action transitions from being completely frozen to constantly running down, creating an almost arcade-y sense of franticness and on-the-fly decision making; to be confronted with the fully “unlocked” battle system at the top of the game would surely overwhelm most players.

Lastly, Resonance of Fate took a stride in the opposite direction, opting for a system in which attacks have the cinematic appearance of “gun fu,” though the phase before executing an attack is entirely static. As realistic as the character models and environments feel, the planning phase of any given combat turn is completely abstract, with the main method of damage-dealing involving characters having to move in straight lines that intersect with one another. The disparity of the filmic attack sequences and the entirely conceptual and “game-ified” planning phase is remarkable, and is a pinnacle of turn-based JRPG combat innovation to the extent that I personally could not get anything done in battle without extensive tutorial-searching and experimentation. While one might imagine the same system existing on previous consoles, it seems that such a bizarre combat system could only be sold once the player could be rewarded with spectacular moments of stylized gunplay, thanks to the seventh generation hardware.

As an aside, fully-rendered HD character models only rarely have graced the traditional, turn-based RPG, with Lost Odyssey being one of the only titles that comes to mind. Gorgeous as the game’s world is, seeing a party of lifelike character models standing idly in a three-dimensional environment while a massive dragon snarls at them requires a generous suspension of disbelief.

The other major inspiration for innovation in the seventh console generation is attributed to the new options of control available on Nintendo’s hardware, specifically the Nintendo DSi’s touchscreen and the Wii’s motion controls. Stylus-based interactivity did not fundamentally change the mechanics of many major IPs — both Zelda titles on the console would deliver the same experience with a traditional 2D Zelda control scheme — but it was crucial for new IPs, most notably The World Ends with You and Sting Entertainment’s Knights in the Nightmare.

The World Ends with You utilized every aspect of the DS hardware. The dual screen setup was tapped by a battle system that forces the player to alternate between two different perspectives on the combat scenario, one controlled by specific stylus actions (tapping, slashing, encircling) and the other controlled by the directional pad. This in itself is unprecedented, though the game took it even further by having certain skills require the use of the system’s microphone and other features. The result is a captivating, adrenaline-pumping development of the ARPG, facilitated entirely by touchscreen controls.

Knights in the Nightmare, rather than expanding existing playstyles on the new hardware, is one of the most praiseworthy examples of fusing incongruous genres to create something entirely new. As a grid-based tactical RPG controlled by a stylus, at first blush it’s no different from playing with a mouse; however, enemies assault not your soldiers, but your cursor itself. The result is an overlaying of bullet hell onslaughts that literally impede your ability to get anything done, as all commands must be executed by navigating the on-screen interface with your cursor. This is only the essential mechanical concept of the game; other twists and variables, such as stark limitations on unit movement and nonsensically-shaped hitboxes (ironically recalling something as traditional as chess), give the experience both depth and contour and necessitate perhaps the most lengthy unintegrated tutorial in any game. While such a feature may deter some players, it is a small price to pay as an entry fee to one of the most forward-thinking and bravely experimental titles on any platform.

The JRPG’s flirtation with the Wii’s motion controls was perhaps less robust but did produce the fascinating The Last Story, which attempted to marry the story-driven genres of third-person action-adventure and RPG. The only real control innovation was that of motion control-based aiming (née “light gun”), but this alone helped immersion and enhanced the three-dimensionality of some of the game’s most impactful set-piece encounters.

In recent years, the tradition of innovation has dwindled on the home console front and certainly slowed even in major titles on handhelds. No doubt that this corresponds to the rising costs of development in proportion with the ever-increasing power of both types of systems. Not since Xenoblade Chronicles has a major, new console IP with its own fresh take on combat come on the scene and proven its staying power. The Tales series’ combat recently feels like it moves obliquely rather than forward into new territory. Even Valkyria Chronicles 4, the first true follow up in a decade to the critically-acclaimed — and very innovative — original title, betrays a hesitation to really experiment or build upon its systems, even going so far as to step away from certain new elements introduced in the interim titles. (I, for one, would love to see this series incorporate dodge rolls that drain AP but cancel interception fire for a brief window, increased verticality in level design, and proper stealth kills.) There is some slight reason for hope in the small developer and indie scenes, with titles like Child of Light and Exist Archive picking up on Grandia and Valkyrie Profile’s systems, respectively, and even Undertale introducing its cult following to a shrewdly simplified variant of Knights in the Nightmare’s mechanics — yet these types of titles tend to simply replicate long-abandoned battle systems rather than truly innovating (Metroidvania burnout, anyone?), and they are not prominent enough to recreate the healthy sense of competition that helped experimentation move to the forefront of the genre in previous generations.

Of course, not all dramatic innovations are successful. The Caligula Effect and Natural Doctrine are depressing evidence of this, as is the unshakeable “black sheep” status of the SaGa series, though it does indeed have a following. In these cases, it is often a failure of the game’s overall design or balancing to capitalize on that which makes it unique. During my own playthrough of Caligula, I contrived an encounter with four lower-level foes and experienced, for the first time, a need to use all the tools at my command while fully embracing the specific rhythm of planning and executing. I was rewarded with a perfect balance of risk vs. rewards; for that one scenario, the game became an enthralling and fun twist on positional strategy and timing. Yet in the normal flow of progression, encounters were limited to one or two foes at a time and these enemies were so bullet-spongey that any given turn felt the same as the previous one. This shows that the innovations themselves remain compelling and even successful; the game built around it, sadly, obfuscates that fact.

It is hard to assess whether or not experimentation in JRPGs has actually begun to recede. Most of the great series discussed here have not seen new entries on modern consoles, and many are being demoted to free-to-play mobile games for their next outing (Valkyrie Profile and Wild Arms, for instance). This trend suggests that there is a fanbase still to be mined for cash but that the development of full, new titles is not worth the investment in time and labor. This is likely due to the exponentially-growing cost of generating unique assets that take advantage of modern hardware well enough to be competitive. Octopath Traveler points to a potential solution, one that first manifested with the success of Bravely Default: the versatility of the Nintendo Switch gives it the potential to be a home for games that feel at once modern and retro. If Octopath Traveler is positioned as a Final Fantasy VII of sorts, I would be very excited to experience not only its sequels — assuming they are innovative (Final Fantasy VIII) rather than iterative (Bravely Second) — but also a variety of neo-retro titles that respond to it with their own combat twists along the lines of Star Ocean, Valkyrie Profile, and Grandia. We might then hope for a new, thriving ecosystem of JRPGs that are at once symbiotic and competitive with one another.

Image Sources: neogaf.com, ds.gamespy.com, obscurevideogames.com, videochums.com, eldojogamer.com, powerupgaming.com, gameranx.com, justpushstart.com, resetera.com, venturebeat.com, neoseeker.com, reddit.com, giantbomb.com, eurogamer.net, inmotiongaming.com

What an awesome feature. I loved it! Thank you.

thanks for reading!

Personally I’d much prefer reused assets and favorite battle systems done to death! Loved Bravely Second doing pretty much what Bravely Default did. And I loved the small changes that then spawned Octopath Traveler (which no, doesn’t remind me of any old game, just of Bravely games). Then again, I’m far more of a fan of Dragon Quest that hasn’t enjoyed a Final Fantasy game in almost 2 decades haha, so I’m not your average JRPG fan.

Nice post!

Thanks for reading! I never managed to get into a DQ game honestly but I’ve got my eye on the Switch version of the latest installment, whenever that happens, and am hoping to get pretty lost in it.

I enjoy both innovation and reiteration, and tend to enjoy different series based on that. Pokemon and Fire Emblem are two of my most beloved series, and they generally only change a little between games. I love the Department Heaven series for how different its entries are. I’d really like it if a new game could come out for that series already. And while I haven’t played very many games in the Megami Tensei metaseries, I find it fascinating how that has spun off in many ways and innovated. Look at how different the Majin Tensei and Devil Survivor games are from each other, despite both being tactical RPGs.

So yeah, major revolutionary changes can be great, and so can steady evolution.

A good balance of innovation (all the different Mega Ten) and comfort food (Pokemon & FE) is a nice way to go about gaming, yes!

Totally. The YS series is doing this really well right now, I think. The only real change between VII and VIII is the camera angle, and it really does a lot to bump the series forward. IX looks like it’s even going as far as adding different means of traversal so I’m looking forward to that.

Great feature. I think I’d add that another thing that RPGs provided in the 8- and 16-bit era that was sorely missing from platformers and shooters – apart from innovation – was the attempt to weave story into the gameplay. Other genres have caught up now to a great extent, but an RPG was really the only genre that helped you feel like you were exploring another world. I think that’s what kept pulling me back, as much as the varied combat systems (and the dopamine thrill of powering up level after level).

Great article, and great summary of JRPGs! I was just thinking about this recently, and pondering what the future of JRPGs is. Especially with the rumblings and news about the new generation of consoles, right around the corner…

A bit late, but wanted to say I enjoyed this piece. JRPG series games come out less often these days (FFI-VI, 6+ years; FFVII-X 4+ years; FFXII, XIII, XV 10+ years), which means greater risk for innovation and slower evolution. The risk of not innovating is eventual lower sales (usually due to outside competition), but consumers are still buying for now.

I don’t need FF to become an action-adventure RPG or Trails to become a graphical juggernaut. A series can be true to what it is and still innovate somewhat (as this article indicates). That said, these days big jumps in innovation will likely come from new IP that are not bound by tradition.