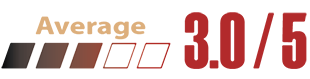

Long Gone Days Review

Neat and Tidy War

War is messy. There are many aspects of it that cannot be fictionalized easily. Media has long tried to show every aspect of war, in some cases romanticizing the heroics of it, in others using analogies, both subtle and overt, to highlight the horrors that can come from it. Developer This I Dreamt’s Long Gone Days takes a lot of thoughtful approaches to the problems that war can bring in the multilingual world that we live in. When factoring in the heavy subject matter, there are a lot of undertones that do not push the narrative far enough to be truly poignant. There’s too much that’s wrapped up in a neat little bow to let the heavy moments really sink in before moving along. With the heavy moments being breezed by, a lot of the game gets left in the enjoyable turn-based combat, visuals, and music that all heighten the experience, but ultimately feel counterintuitive to the anti-war themes presented.

Long Gone Days follows the story of Rourke, an aspiring sniper who has grown up underground in a facility called the Core. The Core is led by Eugene Weisner, who styles himself the Father General to all those that live there. Life in the Core is minimalistic with food luxuries limited to protein shakes, training being the only way to pass the time, and the strongest being the proud chosen few to go and liberate the surface world. The surface world is a fictional version of modern society, complete with real countries and languages used. This added realism enhances the game as it’s interesting to see other languages used as a way to show how multi-lingual society has become. The Core has made a name for itself in this world as an entirely self-sufficient state that creates jobs for everyone with a society that is purely bred and raised in the Core with no outside influences. This leads to many in the Core to be brainwashed solely in the ideals of the Father General and trained in warfare to back those sentiments up to the world at large.

Rourke is selected to join the elite Raven Squad as a sniper, replacing the injured Sergeant Coyle. The rest of the squad scrutinizes Rourke as Coyle is well regarded, and Rourke’s attempts to befriend the squad’s medic Adair are rebuffed at the start. This solidifies Rourke’s thoughts that fulfilling the Father General’s will is the most important aspect and camaraderie comes second. His first operation is to snipe some malcontents that took over an area and make it clear for citizens again. That is until Rourke finds out that these “malcontents” are just civilians living their lives and the Core are the invaders. When the squad commander murders a child in front of him, Rourke begins to second-guess his life decisions. This spiral leads him to leave the Core in an attempt to atone for his actions.

What follows is a look into the psyche of a soldier made to fight for a cause that they don’t believe in and how to atone for their past. These heavy and hard-hitting moments are meant to be poignant, but they are undercut by a narrative that is rushing to a conclusion or not diving deep enough to match the context of the situation. In addition, balancing too many moments at once leads to the urgency of the situation not lining up with what’s happening to the characters.

Long Gone Days also takes a look at how language barriers can cause problems. Three languages other than English are used throughout the game, depending on which locale Rourke finds himself in. Each instance amounts to Rourke internalizing the wish that someone understood him, and then finding the one person in town who helps solve the current problem. If this mechanic had been tied more closely with the game’s themes of war, perhaps it would have come across better. There’s only one small instance where the language barrier causes a tragedy, and that is shunted to the side and relegated to a sidequest that can cause morale loss for a party member. There’s a lot of mileage that can come from language barriers as a narrative device, but its execution is minimal in scope for the plot and the development of the characters.

Morale is also a system that feels underutilized in Long Gone Days. Characters can gain morale by helping NPCs found along the way by completing sidequests so they’re better prepared for the upcoming attacks. Other than showing a green plus or a red negative for choices made, there’s no tangible way to keep track how morale is changing. If it changes options in the story there’s no indication that other plotlines are missed out on as a result. There is a lot of emphasis on this mechanic and many of the quests, including the main story, have moments that indicate a morale shift, but nothing to justify why it matters.

Combat is infrequent in Long Gone Days and always scripted. There are no experience points to grind, as characters gain new abilities and boosts in stats from plot progression instead. Customization to stats is still possible with equipment, but outside of accessories most of it is just upgrades to what the character is already using. When combat does appear it is with enemies shown on the map. Avoiding enemies can fit the themes at play, with the party infiltrating an enemy headquarters that has civilian militia in it. This affects Rourke verbally, but mechanically avoiding combat doesn’t change anything. In fact, exploring elsewhere to fight more just gains the party more treasure, both from combat and chests. Counterintuitive to the themes in the game, each battle, by virtue of being scripted, also comes with one of two options for rewards, replenishing some skill points, or an item. Sometimes these items are unique to that combat, which causes avoiding combat to make these parts missable, even though avoiding combat feels like something that thematically should be more rewarding than taking out everyone on screen.

As combat begins the typical character portrait versus animated 2D drawings of enemies view appears. These enemy designs are quite detailed and a bit larger than the typical combat models, making them stand out. Turn order is determined by speed with characters choosing between attack, skill, and item options. Items are primarily healing, but a few grenade options are thrown in as well to damage or debuff enemies. Skills vary between healing, buffs, debuffs, and attacks. Skill attacks are guaranteed to hit with percentile only affecting debuffs. Regular attacks have the player choose body parts to aim at that can cause different effects. For example, head shots do more damage but are less accurate, and shooting at the arms can give a small chance of paralyzing targets for a turn. These little details make each encounter varied and show the care given to the game. Character personalities factor into the combat as well, with one character that’s new to using guns being unable to aim at any body part. A shoutout must be given to the character who abstains from fighting entirely. Not only is the attack option swapped out for a boost that can randomly give a buff or heal a party member, but the combat items are unable to be used as well. Overall, while avoiding combat fits the plot, engaging in them is rarely an issue and battles tend to be easy, even though some bosses can hit like a truck.

Everything on the screen in Long Gone Days has a purpose for being there. In some cases it is as simple as visual touches that make corridors and rooms feel more realistic, while sharp eyes notice something that stands out. This usually means it is important to a side quest or leads to more treasure. This makes exploration rewarding when paying attention to all the little details in an area. Visuals do have their crutches as well though; as an NPC can be concerned for a friend they haven’t seen in weeks that lives less than a block away from them. There are also moments where story scenes occur and a loading screen cuts into the narrative to show a short motion comic style before transitioning back to where it was before. These scenes show more than mere words could, but are also jarring at the same time, making it a wash in how impressive and necessary they are. The soundtrack can get lost in the shuffle as it is on the quieter side, and is often difficult to hear during the narrative. However, in isolation each track brings a lot of punctuation to its surroundings, such as aiding the tranquillity of a relaxing location.

Long Gone Days is ultimately a case of tempered expectations. The combat and visuals have little details that show a lot of care has gone into everything. The scope of the story is where the snag comes in, as too many hard-hitting moments get lost in the brisk pace that it attempts to juggle everything, making many of them fall flat in execution. This can be disheartening as there’s a nearly constant feeling of wanting them to do more with what they’re providing. It can be a lot to get past but, taking the game at face value the story beats still flow well enough and tell a good story providing moments that players can reflect on. The adventure is quick and has fun gameplay moments, so it is a perfectly satisfactory way to experience a well-intentioned story.

Disclosure: This article is based on a build/copy of the game provided by the publisher.

Combat is basic but enjoyable

All of the visuals on screen have a reason to be there

A lot of deep subjects are discussed...

... It's just a shame they rarely go deep enough

Good soundtrack can get lost in the background

The morale mechanic is poorly defined

Recent Comments